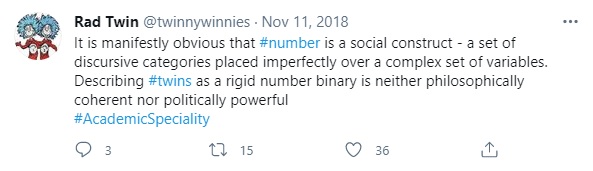

I set up the Rad Twin Twitter account in the summer of 2015 in order to illuminate the increasingly outrageous demands of transactivist lobby groups.The point was to be funny whilst doing it, and it was easy: there was so much material to send up: an embarrassment of riches. I shared the password with my twin sister so we could amuse eachother by trying to outdo the other in how outrageously serious we could be in our quest for ‘twins rights.’ In the intervening years the situation depicted by the demands of the ‘twinnywinnies’ has so nearly come to pass that it is sadly no longer funny. There is nowhere to go with this satire. Completely ridiculous demands, such as that twins be allowed to play in goal together in football, or ride a tandem in cycling (because there is #NoAdvantage), no longer work as parody in the era of Laurel Hubbard, Lia Thomas and Emily Bridges.

Along with the decrease in hilarity, ‘trans rights’ have become so divorced from reality and so demanding that, well, ‘twins rights’ start to look like not such a wild idea after all. The comparison between twins and trans is not purely one of alliteration. It can be used to look at the line between a minority group’s expectation that society attempts to accommodate them and their particular needs, and the need to take personal responsibility for your own challenges.

Twins are one of the last minority populations in the world which haven’t yet had a progressive movement dedicated to them, despite the outrageous singleton-normativity of everyday culture and society. Around 1% of the global population is twins, and about a third of these are identical or monozygotic twins. The population is bigger if you include all multiple births, but in any case the size of the identical twin population is roughly comparable to the estimated trans population, at 0.3%. Despite this, sadly, nobody has ever designed us our own flag. Like the trans population, the twins population is growing. The choice of many mothers to delay childbirth, coupled with the rise in the use of IVF treatments, has led to more multiple births, including fraternal twins, triplets and larger multiples. The monozygotic twin population remains stable though, as it is unaffected by either of these trends. (Clearly we are the really special ones…)

Twins are uniquely placed to understand people with gender dysphoria because there is a surprisingly large overlap of concerns. The first and most fundamental is the issue of identity. For people with gender dysphoria it is well-documented that an internal sense of self is experienced as being at odds with the outward body, and that this is interpreted as being about gender. A congruent sense of identity is therefore lost, and whatever your political beliefs about sex and gender, this is undoubtedly a painful and sometimes unbearable experience for a small number of people. We may disagree politically about the best treatment, whether psychological or medical, but the fact remains that it becomes untenable to stay as you are. As a twin, identity is also at the forefront of mental health concerns, although it’s only conjoined twins for whom surgery is an option. The rest of us have to make do with mental health services which have no specialist training and treat twins as if they were the same as two singletons. For some twins the enmeshing of identities is so impossible to live with that the only answer is estrangement. Identical twins will move to the opposite ends of the earth to escape one another and attempt to get away from the insurmountable identity problems which being a twin engenders. It’s really not the same as being two singletons.

The problem for many trans people is that if you don’t pass as the sex you feel you are inside, random strangers are liable to ‘misgender’ you in the street. I understand the pain of being reminded, everywhere you go, of an identity which isn’t yours and which you may have rejected. However, the notion of gender is only one aspect of your identity as a human being, so, however distressing it is, it cannot be quite as annihilating as having your whole identity mistaken over and over again, so that it is your whole person which gets obliterated, not just one aspect of it. Rad Twin would surely claim that twins have it worse. If only we had one of those lovely activist groups working on our behalf, then calling a person by the name of their twin sister would be a hate crime by now, and half the attendees of the Women’s Liberation Conference 2020 would have a criminal record.

The popular image of twins, particularly children, is mischievous, naughty and cute, which makes it difficult to see a different picture or to get across the downside. To twins themselves growing up, it’s a form of brainwashing. With any other marginalised community we might call it ‘stereotype threat’. So pervasive is the public perception that it seems almost churlish to disabuse anyone of their belief that being a twin is nothing more than having a best friend for life and who wouldn’t want that? Trans people might set great store by their inner ‘identity’ but what if there is no individual inner identity to defend? Brought up on Bill and Ben, Pinky and Perky and Tweedledum and Tweedledee, and dressed identically throughout childhood, it is clear to an identical twin right from the start that the only identity available is as part of a unit. We never hear about Bill, Pinky or Tweedledee on their own. Even the thought of it is slightly embarrassing, somehow inappropriate. So strong is this indoctrination that twins themselves can find it too threatening to contemplate. And don’t even start me on pronouns. Insisting on other people referring to you as she/her is the height of singleton privilege when your pronouns have been they/them for as long as you can remember, entirely without your choosing.

Today’s emphasis on being your ‘true authentic self’ presupposes there is a true authentic self to be. To an extent everybody’s sense of self is a work in progress, but as an identical twin, born and raised as a unit of two, the notion of an authentic self is in itself a prime example of something only singletons can take for granted. Popular psychology in the form of magazine articles, books and agony columns have never been any use to twins, with their emphasis on being ‘who you really are’ and their insistence that you are unique, there is only one you, and therefore you should strive to be yourself rather than copying anyone else. Comparing yourself to others, or the belief that you are being compared, is written into the DNA of identical twins, it’s not a choice. Academic psychology fares no better and has little to say about twins. Some of the more established developmental theories, such as attachment theory, fail to take into account the developmental repercussions of attachment to a twin as well as to the mother. It’s possible that twins develop differently to singletons. Seeking to understand yourself as a twin, you will find there is no informed help out there. Somewhat ironically, if you’re experiencing problems, you’re on your own.

Media representation is a constant bugbear which trans groups campaign about. Just as transsexual males have often in the past been the butt of jokes, identical twins are usually portrayed as a bit of a lightweight gimmick. When twins are not an amusing novelty they are invariably a sinister threat. We go straight from The Shining to Jedward, with very little in between. Trans groups have complained about the lack of trans actors playing trans roles in films and TV but this is nothing compared to the habit of using one actor to portray both twins, such as Tom Hardy playing both the Kray twins in Legend or Lisa Kudrow playing Phoebe’s twin sister in Friends. The lazy cliche of interchangability makes for entertaining viewing, but it is the source of existential crisis for real twins. The most recent culprit was the Norwegian drama series Twin, which not only used the same actor for both twins, but had a storyline which suggested that an identical twin is so identical that even their own families would not be able to tell the difference. This is a completely unrealistic and gimmicky stereotype, but at the same time it is the stuff of nightmares for twins. What is the point of your existence if you are so completely interchangeable with someone else? I don’t know why it isn’t taken more seriously, but it isn’t. People just find it entertaining.

The publishing industry, under great pressure from trans lobby groups and allies, has greatly increased its representation of trans people’s lives, both in children’s literature and books for adults. The same attention is not given to twins. I grew up with old-fashioned stereotypes such as Enid Blyton’s The Twins at St Clares, with its twin-based pranks and mischief. As an adult I progressed on to the casual bigotry of books like Dostoevsky’s The Double:

“Good people live honestly, good people live without any faking, and they never come double.”

The blatant twinsphobia here remains unchallenged to this day and the Society of Authors does nothing.

In representation more broadly twins remain marginalised. Whereas trans people are gaining a higher profile in politics and journalism, twins remain largely unrepresented, apart from in entertainment, where acts such as Bros, the Proclaimers and Jedward capitalise on their USP. The politicians Angela and Maria Eagle are the only twins in public life in the UK who buck the trend. There are no specialist twins groups in political parties, nor even specialist NHS groups or counselling organisations. If you try to find twins support groups you will find many groups designed to support parents of twins and the odd ‘lone twin’ group for people who have suffered a twin bereavement, but nothing for adult twins living in a world made for singletons. You might come across TwinsUK though, which uses twins for research and are therefore the experts, but you will find they have no interest in research which benefits twins themselves, or support for twins or any knowledge of where to look for it. There is a long and disturbing history of twins being exploited for research, and the modern manifestation is obviously benign by comparison. If you have voluntarily contributed to this research there is nothing to complain about, but still it niggles that there is not more recognition in the scientific community that twins themselves might benefit from different areas of research, and that twins too are important. It is still almost impossible to find any quantative data on twins as a distinct demographic.

There has been a recent social media controversy over the role of trans people in the Holocaust: were trans people targetted in the same way that homosexuals were, or were some of the Nazi officers themselves cross-dressers or possibly transsexual? There may be evidence on both sides, but in general the re-writing of ‘trans history’ has been criticised by women’s and gay rights groups, as more and more historical figures have been retrospectively transed despite a lack of evidence. There is no such need to embroider the truth in the history of twins. It is well known that twins were used for medical experiments in the concentration camp at Auschwitz, and uncontestable that social experiments in the fifties and sixties resulted in the deliberate splitting-up of twins and triplets so they could unknowingly form part of research projects. If the definition of oppression is the exploitation of a class of people for the gain of another class, then twins have a realistic claim on a society which has exploited their unique genetic inheritance more or less from the time it stopped killing them at birth. The benefit to singletons has been immense, from medicine to the social sciences to psychology, everyone benefits from experiments on twins and research projects featuring twins. You would have to look a long time before you found a project designed to benefit twins themselves. Nor is there a Twins Day of Remembrance to honour those lost.

Trans rights groups are always banging on about pronouns. Words conventionally used to denote sex are being repurposed to represent ‘gender’, for the benefit of 0.3% of the population. The demand that people put their pronouns in their email signatures or Twitter bios is defended as a nod to the idea that we cannot always tell someone’s ‘gender’ from their name or appearance, whereas in reality of course we can tell someone’s sex with almost unerring accuracy. This is an unrealistic expectation of the majority. In my quest for my twin identity to be always recognised and honoured I could claim that nobody’s ‘number identity’ should be assumed on a first meeting and that therefore it should become normalised to ask every new aquaintance whether or not they are a twin. Singleton status should not be the default because it ‘others’ those of us who are twins. (I think that this was in fact one of the first demands of Rad Twin on Twitter, and, rather winningly, some of our early allies agreed to it…)

The damage done to minority groups through misrepresentation and marginalisation can be serious. To some extent we are all subject to the pressures of the perceived ‘normality’ of the majority. Minority groups deserve advocacy and deserve to be seen. The reality though is that the majority will always be the default setting, and however hard it is, minority groups cannot expect to become the default themselves. At best they can become more visible and more people will understand them and treat them well. The fun of Rad Twin was in imagining a world where twins became the majority voice in all policies and public discourse. It was funny because it was ridiculous. And this is where I part company with the demands of extreme trans rights groups, who cannot see how unrealistic it is to expect that everybody else resets their instinctual and very human propensity to see and respond to averages and patterns, in favour of the demands of outliers. In reality nobody can live like that. It can be difficult to live as a twin in a non-twin world but the non-twin world is never going to prioritise twinship for my benefit and I wouldn’t presume to demand it. There comes a point where having your every demand indulged only serves to infantalise and you have to learn to stand on your own two feet. Or four.

Being part of a minority group can be a lonely place to be. If you have basic human rights which protect you from discrimination, and support groups which advocate for these rights, then the law on its own cannot do much else for you. It is up to you to find the support you need and to advocate for services particular to your needs and to encourage education which will help with other people’s understanding so that you can live amongst the majority without too much friction. Any more than that and you enter a realm of unrealistic and sometimes ridiculous demands which only serve to alienate well-meaning bystanders who have concerns of their own which they may need to prioritise. Demanding that everybody else must change their language for your benefit or that children must be taught your feelings as fact is a step too far. No amount of empathic understanding warrants the world being turned upside down to benefit one tiny group of people at any other groups’ expense.

To illustrate the point you only have to think about all the identical twins you know, or have ever known in your whole lifetime. Then imagine that all the language you use to describe yourself has to be changed just to keep this tiny group of people happy, and that every new person you meet is just as likely to be a twin as not and you have to check this with them every time before you can even address them. You might begin to feel this is disproportionate, and that’s before we even get to the bit where you have to lose your safe spaces and sports. My sympathy diminishes even more when the ‘gender dysphoria’ part of being trans gets taken out of the equation, as has been lobbied for by all the organisations fighting for ‘self-ID’. Natural empathy for existential identity distress is impossible to extend to the fetishists and fakers now welcomed under the trans umbrella.

Twins of course are not usually beaten up for being twins (except for that one time in primary school when the local thug just didn’t like the look of us…) and we can always pass as singletons if we keep out of eachother’s way. Even Rad Twin would stop short of demanding that twins become a protected characteristic in the Equality Act. Some sensitivity in media representation and entertainment would be accomodating though, and whilst not asking for a 46-page school twins toolkit to explain us to the educational community, some early years policies in education could be of benefit, if only to counteract the ubiquity of the doppelganger myths and cliches identical twins have to grow up with, and to facilitate more understanding from normal people.

In case it seems like I’m complaining, I should make it clear that being an identical twin is obviously the best thing ever. #TwinsIsBeautiful as they say on Twitter (or something like that). You singletons don’t know what you’re missing: for me, life is unimaginable without a twin sister to share it with. The downside though can be brutal. So although the popular conception of twins can sometimes match the reality, it’s not always as much fun as it looks being born in two bodies.

Rad Twin though: that was fun while it lasted 😉